The last months were filled with a heated public debate on whether academia should be seen as ‘topsport’ (the Dutch term for professional sports). Funnily, right before these public discussions, we had our own local discussions with proponents of the topsport analogy. After thinking a lot about this complex topic, we will argue in this post that viewing science as competitive sports is not only unfavorable but even harmful for the individual researcher and science as a whole.

The ‘Topsport Analogy’

First, a brief recap of the recent public debate: It got kick-started by an interview with virologist Ab Osterhaus in early June. During this interview, he expressed his view of research as highly competitive and that this competition keeps the quality of output high. He also views being a researcher not as a regular 9 to 5 job, but as something that requires more drive and dedication ….just like professional sports. We couldn’t help but wonder: do more people think that a good researcher should perform just like a professional athlete?

Indeed, it looks like more people share this opinion. The head of the Dutch Research Council (NWO), Marcel Levi, also describes research as fierce competition, involving rivalry and many working hours. Although he does acknowledge that science often also requires team effort, his statements lead to another important question: If the head of the Dutch research funding institution views science like professional sports, what does this view imply for how we practice science and what we require of researchers?

Research as Competition

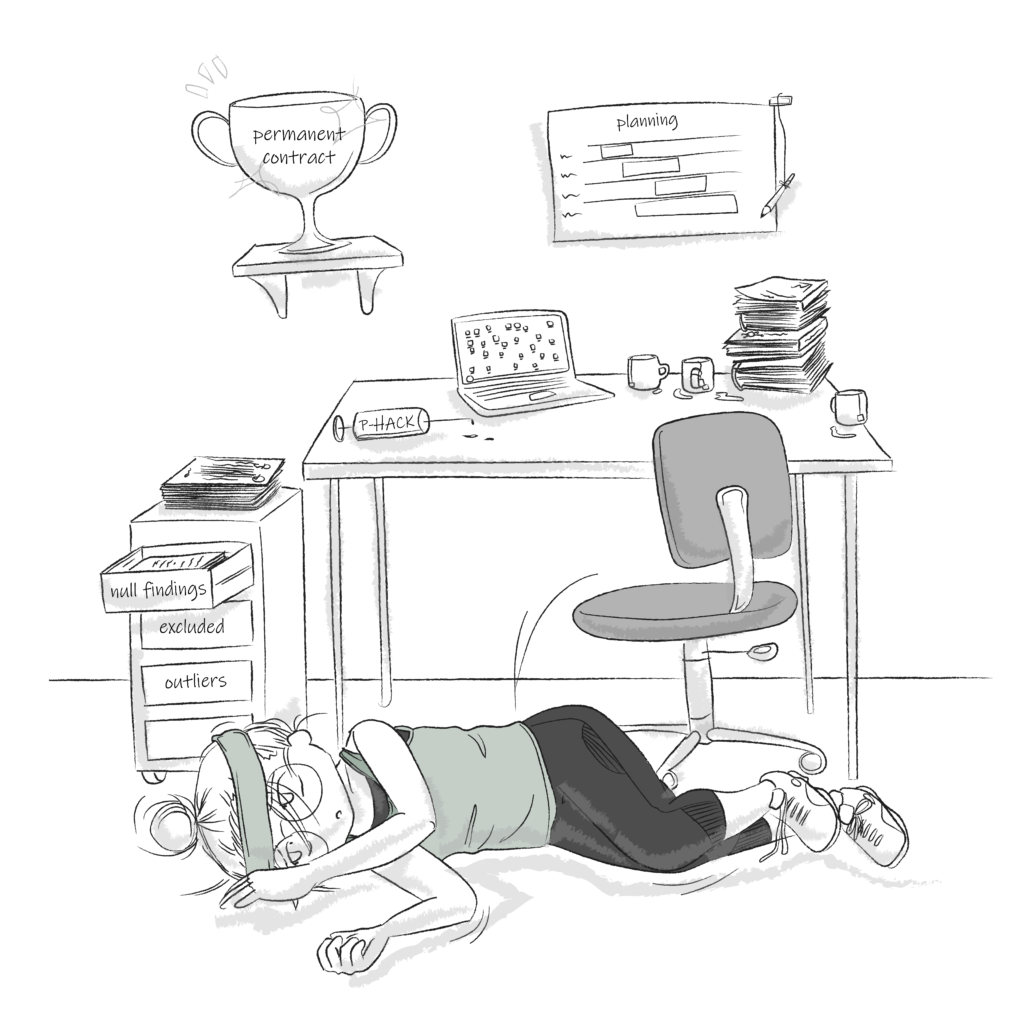

Currently, we ask a lot from researchers, arguably we ask them to work multiple jobs crammed in one position. Plus, research positions are scarce, creating intense competition. To determine who succeeds in this competition, researchers are evaluated on their research output, including the quantity of publications and obtained grant money. If you want to check this yourself, browse some vacancies on Academic transfer and Jobs.ac.uk. Broad vacancy requirements with superlatives such as “demonstrating research excellence” and having “an outstanding”, “distinguished” research record, create extreme pressure for the researchers trying to stay in the system.

On top of this already existing pressure, proclaiming science as competitive sports reinforces an arguably toxic system. For the individual, the focus on competition and ‘winning’ fosters a number of harmful behaviours associated with negative consequences for mental health (e.g., overworking, sleep deprivation, personal misconduct, or abuse of power). This shows also in actual professional sports: professional athletes Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka recently drew attention to the detrimental effects of excessive competition on their mental health. They shared suffering from depression, anxiety, and a loss of meaning after the long period of intense competitive pressure that came with their sports career. However, unlike researchers, professional athletes have a whole team around them to care for their physical and mental health, plus their career lasts maximally into their 30s.

For us, it seems that maintaining a system in which employees work on the limit of their capacities is neither desirable nor sustainable for academic advances. We think that the fact that (social and behavioral) science is suffering from inconclusive or unstable evidence (often referred to as ‘replication crisis’) illustrates this unsustainability. Fierce competition inevitably leads to cutting corners, which in turn encourages sloppy science. We would even argue that funding only a few successful individuals and boosting particular popular topics limits instead of encourages creativity and innovation. Still, some people argue that science profits from competition by increasing output quality and innovation.

Why do some prominent people in academia cling to this toxic view?

When the ‘winners’ of this ‘competition’ consider why they were selected, they often suffer from survivorship bias: They consider the abilities they excelled in as crucial for the selection, and fail to see the abilities of people who did not make the cut. Those that are not selected might excell in crucial abilities to the same degree – or may even bring more to the table. For example, some successful researchers might argue that their success is due to their hard work or their resilience. However, this perception is skewed: not only those that receive a permanent position in academia are ‘hard working’ and ‘mentally strong’ – most of us are.

An often unseen factor for success in academia is luck. As explained in this video, especially in jobs involving high competition, we underestimate the influence of luck. This is not to say that skills, talent, and hard work are not important (they very much are!), but so is the popularity of your research topic, the current availability of resources, the people you meet along your career path, the mood of the reviewer when evaluating your paper/grant proposal, or your general privilege.

If the winners of the selection are comparing their performance to professional sports, implying they defeated the competition, this might actually be a consequence of their survivorship bias. Next to the previously explained toxicity for researchers and academia, we think that this analogy is skewed and unnecessary.

Leaving ‘Academia as Topsport’ Behind

Several researchers and journalists have already expressed their disagreement and concerns about the view of academia that the topsport analogy represents (examples in the Dutch media here, here, and here). We fully agree with those statements. We’d especially like to draw attention to this opinion piece that emphasizes that science does not only need ‘star players’, but a larger team with diverse roles. It also calls for more solidarity between researchers at different career stages. Showing solidarity and creating a shared identity as a team just seems tricky to us, if we stay in the sports analogy, in which people view themselves as winners or ‘star players’ because they are skilled at climbing the pyramid.

So what does ‘winning’ actually mean? We think it should mean producing research that is trustworthy and that benefits society. In this post, we argued that viewing academia as professional sports is not beneficial to this definition of winning. We neither feel in the position nor knowledgeable enough to offer concrete solutions to all systemic issues academia is suffering from, but the current debate on the Recognition & Rewards system in Dutch academia seems like a step in the right direction. We provide a perspective of two young, very early career researchers on the system in which we may continue to work – if we are lucky.

Many thanks to our new illustrator Lisa for the amazing illustrations.